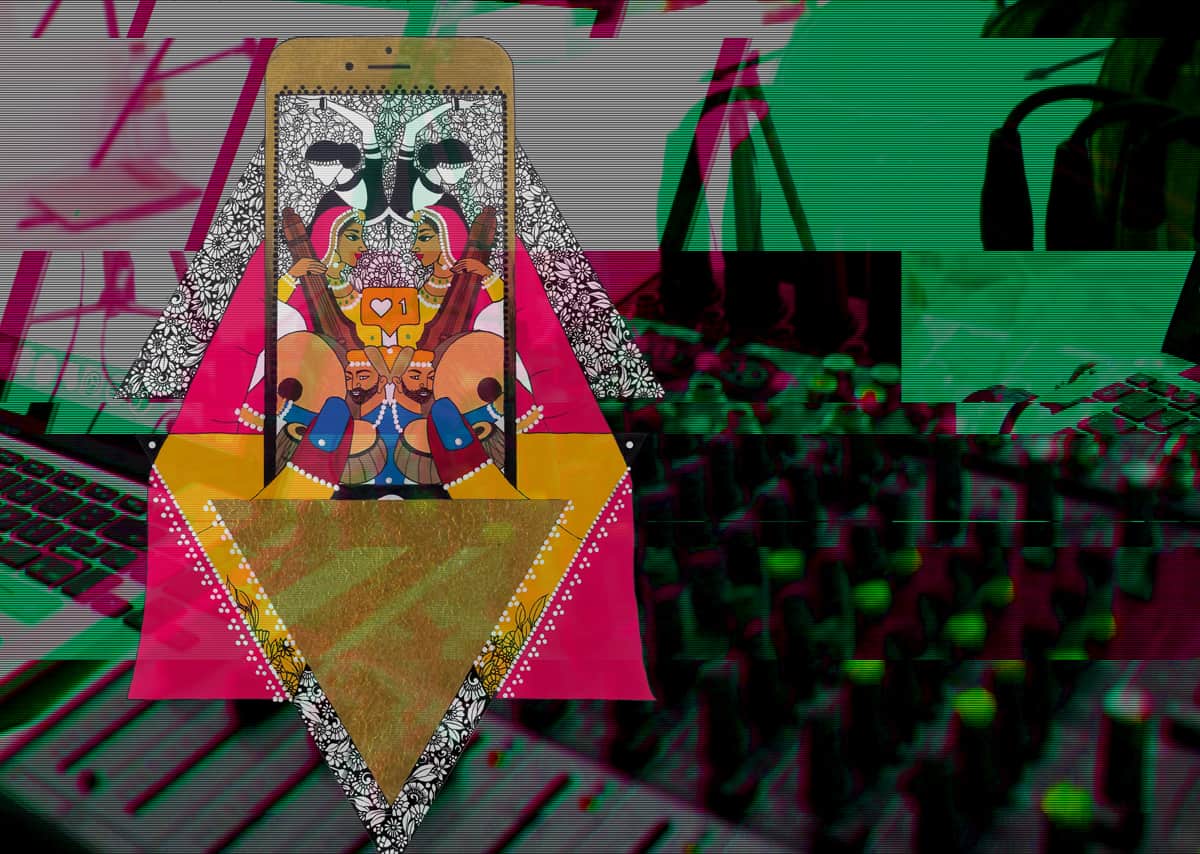

Once upon a time around fifteen years ago, we didn’t have the world at our fingertips. The thing with technology is that it creeps its way into your life without you noticing. Fast forward to the present and it’s impossible to go a day without being digitally connected.

F or creatives, there’s nothing quite like the joy of being able to share your art. Artists can set up their own pages, build a following and share with fans all across the world. Take Ashanti Omkar, for example, a BBC broadcaster for whom social platforms act as a great way to discover talent: “Musicians across the globe reach out to me, be they a rapper in Madurai or a Carnatic musician from Bristol,” she says. “I discover music in many places ‒ Soundcloud, YouTube, Facebook and, more recently, Instagram.”

“…with so many avenues of connectivity, where does one even begin?”

A snap to share a clip of your amazing concert experience, a boomerang of those ghungroo-adorned legs tapping away, a Twitter conversation with your favourite artist – the opportunities are endless. Yet with so many avenues of connectivity, where does one even begin?

The saturation of content is what has driven many platforms to implement algorithms. Gone are the days of chronological timelines. Instead, social networks show you things that are popular, things that your friends have liked, or things that the algorithm thinks you might like. As an artist, sharing your creation online only to have it lost in the crowd of “Check out my…” posts can be disheartening. Carnatic singer Adesh Sundaresan says: “It’s easy to get sucked into the performing bandwagon, or feel as though we aren’t getting as much exposure as others.”

“…sometimes it’s not about reaching the maximum number of people online.”

Kitha Nadarajah, musician and founder of live-streamed concert series Raga Room agrees that there’s a risk of content being lost, but that there’s also more to it: “It’s important to know what purpose content serves and to stay true to that ‒ sometimes it’s not about reaching the maximum number of people online.”

Ashanti has to take this into consideration when connecting with talent. “One can record in a bedroom or in a plush studio, then auto-tune and edit it to perfection,” she says. “These are not the musicians I tend to seek out, even if they are massively popular online. I always do due diligence, and get my team at the BBC to vet the music too. I seek what is credible talent, and that they are an authentic musician.”

“…social media is helping make classical music more accessible again…”

The social media age has heralded new ways to build and nurture relationships. For time-poor, curiosity-rich individuals, it provides the opportunity to learn on your own terms, in your own time, in your own way. Sarod maestro Ustad Amjad Ali Khan even spoke about how social media is helping to make classical music more accessible again, allowing upcoming musicians to refine their skills through the available resources.

Apps such as Sangeethapriya allow students like Adesh to rack up hundreds of hours listening to multiple versions of a song to get a near-360 understanding of a composition. Esteemed classical artists are growing networks of students across the world through Skype lessons, giving passionate rasikas (enthusiasts) the chance to learn from true stalwarts.

“One has to consider issues of lag and sound quality.”

Adesh has been learning from his guru through Skype for years, and while it’s a great way to keep in touch, he can’t deny that regular face-to-face is an absolute must during one’s training. “It does test your belief in yourself when all you have is an audio call. Human beings feed off reactions from others,” he says. “One has to consider issues of lag and sound quality. Beginners need face-to-face guidance over rhythmical aspects. Once the concept of tāla (rhythm) is somewhat understood, it gets that bit easier to learn online.”

Some say that online learning is simply a shortcut and there are many aspects such as posture, rhythm and articulation that are much harder to pick up and correct through a screen. Whether it’s music or dance, there’s a physicality to the art that needs as much attention as the sounds and movements themselves.

“…for dancers…nuances…are much harder to convey through a screen.”

“Some knowledge and understanding is imbibed through the experience of a face-to-face class and through unspoken actions,” says Kitha. This rings especially true for dancers, where nuances such as abhinaya (expressive dance) and even the exact positioning of arms to get those perfect lines are much harder to convey through a screen.

Yet so many are taking to online classes as a way to refresh or improve their skills, and if the ability to connect has given creatives the chance to pursue their passion, is there much reason to deter them?

“My husband has taken up the bass,” continues Ashanti. “And due to the way social media now works, he talks to everyone from Nathan East, to Mohini Dey and Guitar Prasanna to aid his learning.” The thought of being able to strike up a conversation with eminent classical artists would never have crossed our minds previously, but today performers across the subcontinent and beyond are understanding the value of being active online. “By being on social media, the performer does open themselves up to the risk of facing expectations they cannot meet,” says Kitha. “But the positive impacts far outweigh the negative effects of opening engagement between performer and rasika.”

“The relationship between performer and viewer – or guru and student – is no longer one of deference.”

There’s traditionally been a perception that classical performers and gurus are to be seen and experienced on stage only; approaching them ‘outside hours’ wasn’t the norm. The relationship between performer and viewer ‒ or guru and student ‒ is no longer one of deference. While that shift predominantly comes from changing attitudes in the world as a whole, there’s a case to be made for the fact that social media has provided an opportunity to change these perceptions, opening doors for two-way conversations.

Once upon a time around fifteen years ago, we didn’t have the world at our fingertips. Now that we do, can we find a way to create a world in which digital platforms and classical arts can live happily ever after? It certainly seems so.